Why We Don’t Trust Algorithms (Even When They’re Right)

And why it matters to our relationship with AI.

The Intelligent Friend - The newsletter that explores how AI affects our daily life, with insights from scientific research.

Intro

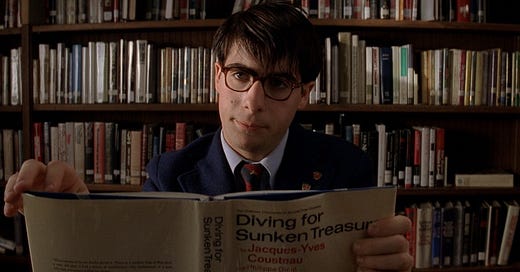

Panic set in. Hours slipped by. Lucas scrolled through online stores, picturing a last-minute boutique stop. Nothing felt right. He needed a present for the birthday party of Matt, one of his best friends. It would have been a surprise party in is apartment in the West Village. He needed something meaningful. Then, a thought. ChatGPT. For a moment, he considered it. But then, he shook his head. No. A gift wasn’t just an object; it was a symbol of knowing someone. And no algorithm could know his friend like he did.

Across town, Francine faced a different hesitation. She had taken the morning off for a doctor’s visit. For weeks, a tightness in her chest had nagged at her—not painful, just unsettling. Dr. White greeted her as always—calm, reassuring. But today, something was different. Instead of his usual clipboard, he held a sleek, unfamiliar device. A diagnostic AI. Trained on millions of cases, detecting patterns even experts might miss. Francine hesitated. Why did he need this? Had something changed? Wasn’t he enough?

Dr. White reassured her. The AI didn’t replace him—it was just a tool. Faster, more precise. But he still made the final call. She nodded, but doubt lingered. She trusted Dr. White. Could she trust the machine? Two people, two decisions, the same question: Could AI really make the right call?

What is Algorithm Aversion?

Whether it was Lucas, resisting ChatGPT, or Francine, doubting AI for her visit, both were having the same reaction. A hesitation. A reflexive discomfort. A feeling that something about using an algorithm felt… off. Both were rejecting a tool designed to help them.

And yet, logically, both systems were capable. ChatGPT could process millions of data points to suggest thoughtful gifts, and Dr. White’s diagnostic tool had been meticulously trained on thousands of medical cases. However, for some reason, people are uncomfortable with it. We are disconcerted by AI. We are negative about it. We are, in essence, averse to it.

Algorithm aversion is the phenomenon where, for various reasons, we are averse to using AI or reject its advice1. It’s a phenomenon that has received a lot of attention in research23 and consumer research4 in particular, and has seen several developments.

The central concept is that, given equal conditions of effectiveness, or even in the case of superior performance, we prefer the result deriving from a human to that deriving from Artificial Intelligence for an activity. Whether it is Francine's diagnosis or the choice of a product, as in the case of Lucas, we are not well predisposed.

And this has absolutely non-negligible impacts. On the one hand, consumers deprive themselves of potentially better solutions in several cases that technology, or its support, can provide. On the other hand, companies often implement options and solutions that consumers are skeptical about or that consumers will not appreciate as expected.

At this point the question comes spontaneously: why are we averse to AI?

The studies that have tried to identify the reasons are different and varied. Today I will rely on a review published in Nature Human Behaviour, by De Freitas et al. (2023) that I find enlightening and very interesting to bring to you also for the clarity of its structure. As always, I will leave you further references for further classifications of reasons and factors that drive our aversion to the algorithm.

Before diving in, one last note. While much of the research focuses on why we reject AI, there is also a growing body of work that shows when we actually prefer AI-generated outputs or advice5.

Some of these situations include6:

When a task is objective rather than subjective;

When people feel less judged by an algorithm than by a human;

When the alternatives are worse than expected;

Well, I'd say we're ready. Why is Lucas reluctant to use ChatGPT's advice for his friend? Why doesn't Francine want to rely on the innovation that Doctor White has so carefully selected and brought into his study, investing time and money in the choice? Let's find out.

1. We don’t understand how AI works

One of the drivers of algorithm aversion is opacity. We are motivated to have explanations - we want to know why a decision was made, how a conclusion was reached7. If a human makes a choice, we can usually ask them to walk us through their reasoning. If an AI makes a choice, this is not possible. In this sense, AI is often considered as a “black box” fo users.

This is why it’s important for many AI-powered products now emphasizing explainability. A clear example is represented by Netflix recommendations: “We recommend this movie because you watched Inception”. There is an effort to explain the rationale of the decision. However, not all explanations are the same. As I wrote in this post on LinkedIn, there are some types of explanations that can even have a negative effect8.

2. Algorithms are unfeeling

We don't think AI has the emotional capacity to manage interactions effectively. We want to feel like we’ve been heard, understood, and cared for. AI, in consumers’ perceptions, still struggles to replicate that feeling9.

A related element that is demonstrated in a context similar to that of Francine example is the consideration of our uniqueness. We are averse to algorithms because they do not take into account our differences, how unique we are compared to others. How can a diagnostic tool be more capable than Dr. White of understanding Francine's problems? This factor is called "uniqueness neglect"10.

Academics, professionals and journalists read analysis like this one on AI and how it impacts our lives every week. Join the community by subscribing for free.

3. AI can’t adapt

Another major driver of algorithm aversion is the perception that AI is rigid, unthinking, unable to adjust to unique situations.

Humans, for all our flaws, are seen as flexible. We course-correct, we weigh nuance, we make decisions based on context. AI, on the other hand, is often viewed as following as incapable of accounting for exceptions. And yet, even if this not actually true, this is how we often perceive it.

For instance, in the study by Reich et al. (2023) is shown that when people are explicitly shown that algorithms improve over time, their trust in AI increases significantly. The study demonstrates that framing AI as capable of learning - either through performance data showing improvement or simply by labeling it as “machine learning” - reduces algorithm aversion and increases user adoption, even in real decision-making scenarios.

4. We fear losing control

If you get into a self-driving car, your first feeling of discomfort is probably that you can’t decide where the car is going. If you use a vacuum cleaner and it doesn’t go where you want it to, you’ll probably be annoyed if you can’t direct it to where you want. If you have a thermostat at home that regulates the temperature, you’ll probably feel better knowing that you can change it whenever you want.

These are all examples of one of the most fascinating (in my opinion) factors that influence our aversion to AI: control (so interesting that I’ll probably dedicate a separate article to it!). As humans, the ability to exercise control over our environment is a fundamental desire1112. In fact, as reported by the authors of today’s article, research shows that those who don’t perceive the possibility of exercising control are more likely to “engage in maladaptive behaviors”13.

This is why it is so important that today, in the creation of AI-based products or features, it is clearly highlighted how consumers can have control over the final result. To account for how impactful this factor is, the simple fact of giving a nickname to an autonomous product14, for example, provides a positive feeling to people.

This becomes particularly important for activities through which we express our identity15. If we love making bread by hand for example, or if we love riding a bike, we will tend to be more averse to products that can impact that activity, such as an automatic dough-making machine or an assisted pedal. If we like driving a sports car and we believe it is important to us, once again we will prefer to have a car with a manual transmission.

I think these results are particularly important to reiterate an element that the authors often report in these studies. As important as technological advances and AI implementation are, we must also focus on not only how consumers think about AI, but also on how they feel about it. This shift in focus allows us to reinterpret efforts and initiatives and orient them more towards people's desires.

5. AI is an outgroup

The final reason we resist AI is almost intuitive: it’s not human. This almost seems superfluous to specify, right? In reality, with advances in the increasingly human-like characteristics of many AI-based tools, this distinction often becomes perceptually less and less.

We see AI as an outgroup of the large group of humans. As reported by the authors, this is driven by the tendency to assign humans greater moral worth than other animal species, called “speciesism”16. Given the increasingly human-like characteristics of AI, according to De Freitas et al. (2023) this tendency may also apply to interactions with AI-based tools.

I hope this issue was interesting or simply you enjoyed it. Thanks as always for reading it,

-Riccardo

P.S. We can connect on LinkedIn or you can write me by email if you like! I’m always thrilled to connect, discuss and meet new people!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If this didn't interest you much, or you'd prefer to read something different, I'd be happy to recommend these recent articles:

Has a friend of yours sent you this newsletter or are you not subscribed yet? You can subscribe here.

Surprise someone who you think would be interested in this newsletter. Share this post with your friend or colleague.

Dietvorst, B. J., Simmons, J. P., & Massey, C. (2015). Algorithm aversion: people erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. Journal of experimental psychology: General, 144(1), 114.

Jussupow, E., Benbasat, I., & Heinzl, A. (2020). Why are we averse towards algorithms? A comprehensive literature review on algorithm aversion.

Jussupow, E., Benbasat, I., & Heinzl, A. (2024). AN INTEGRATIVE PERSPECTIVE ON ALGORITHM AVERSION AND APPRECIATION IN DECISION-MAKING. MIS Quarterly, 48(4).

Mariadassou, S., Klesse, A. K., & Boegershausen, J. (2024). Averse to what: Consumer aversion to algorithmic labels, but not their outputs?. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101839.

Logg, J. M., Minson, J. A., & Moore, D. A. (2019). Algorithm appreciation: People prefer algorithmic to human judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151, 90-103.

Hermann, E., De Freitas, J., & Puntoni, S. (2024). Reducing prejudice with counter‐stereotypical AI. Consumer Psychology Review.

Ahn, W. K., Novick, L. R., & Kim, N. S. (2003). Understanding behavior makes it more normal. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10(3), 746-752.

Mourali, M., Novakowski, D., Pogacar, R., & Brigden, N. (2025). Post hoc explanations improve consumer responses to algorithmic decisions. Journal of Business Research, 186, 114981.

Castelo, N., Bos, M. W., & Lehmann, D. R. (2019). Task-dependent algorithm aversion. Journal of marketing research, 56(5), 809-825.

Longoni, C., Bonezzi, A., & Morewedge, C. K. (2019). Resistance to medical artificial intelligence. Journal of consumer research, 46(4), 629-650.

Leotti, L. A., Iyengar, S. S., & Ochsner, K. N. (2010). Born to choose: The origins and value of the need for control. Trends in cognitive sciences, 14(10), 457-463.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), 1.

Shapiro Jr, D. H., Schwartz, C. E., & Astin, J. A. (1996). Controlling ourselves, controlling our world: Psychology's role in understanding positive and negative consequences of seeking and gaining control. American psychologist, 51(12), 1213.

Zimmermann, J. L., de Bellis, E., Hofstetter, R., & Puntoni, S. (2021, November). Cleaning with Dustin Bieber: Nicknaming autonomous products and the effect of coopetition. In TMS Proceedings 2021. PubPub.

Leung, E., Paolacci, G., & Puntoni, S. (2018). Man versus machine: Resisting automation in identity-based consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(6), 818-831.

Caviola, L., Everett, J. A., & Faber, N. S. (2019). The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. Journal of personality and social psychology, 116(6), 1011.

Control really is a central theme of the human experience. Having an internal locus of control is at the crux of mental health. And yet it is a great and mysterious irony that we fundimentally only have the perception of control - we didn't choose our genes, or environment, let alone any decisions that followed. No wonder hard determinism is so uncomfortable for many to consider, when it is the reality that we all inhabit. AI is very much pulling up this deep rooted reality, that control is a perception, many prefer to ignore or deny. We don't control how AI develops internally, and as these systems develop more agency and ability we likely control them less and less.

My preference is to hold everything I know lightly. Yes I experience having control over my day to day actions (sometimes), but I don't really know this for sure. Sure, I tried to do what I can within my powers to make decisions that help others and myself, and this is that internal locus of control that is very important, but there is a thread of humour that is always with me. A giggle I have with myself, when then and again realise that we never actually had any control to begin with.

Very interesting post! A recent pew report found that something like 63% of Gen Z respondents felt that “ethical AI” was an oxymoron.

I think the idea you’ve developed of algorithmic aversion is particularly concerning in the face of the pressing need for AI governance.

I’m working on a forthcoming piece about how instances of AI systems circumventing human programmed rules signal a deep concern with the strength of the contemporary social contract.

Maybe there is a follow up piece aligning these ideas!