The Intelligent Friend - The newsletter that explores how AI affects our daily life, with insights from scientific research.

Intro

The whale has surfaced. And not only that - it has ridden the wave.

DeepSeek has dominated headlines in recent weeks. Not just in sheer volume of coverage, but in the breadth of perspectives it has sparked. Most discussions have revolved around the technical fundamentals. How does DeepSeek work? What makes it different? How does it deliver high performance while reportedly costing a fraction of its competitors?

However, in approaching to this discussion, I wanted to use a different lens, focusing on the perceptions of users. How does this story unfold from the perspective of the “ordinary” people? What does this frenzy of reporting and debate mean for perceptions of AI itself? Is DeepSeek’s open-source (or open-weight) nature just a technical feature, or does it subtly shape the way people experience and trust the product? How has DeepSeek been framed in media narratives, and how might that influence the way consumers engage with it?

Let’s dive in and meet the whale.

What has been said about DeepSeek?

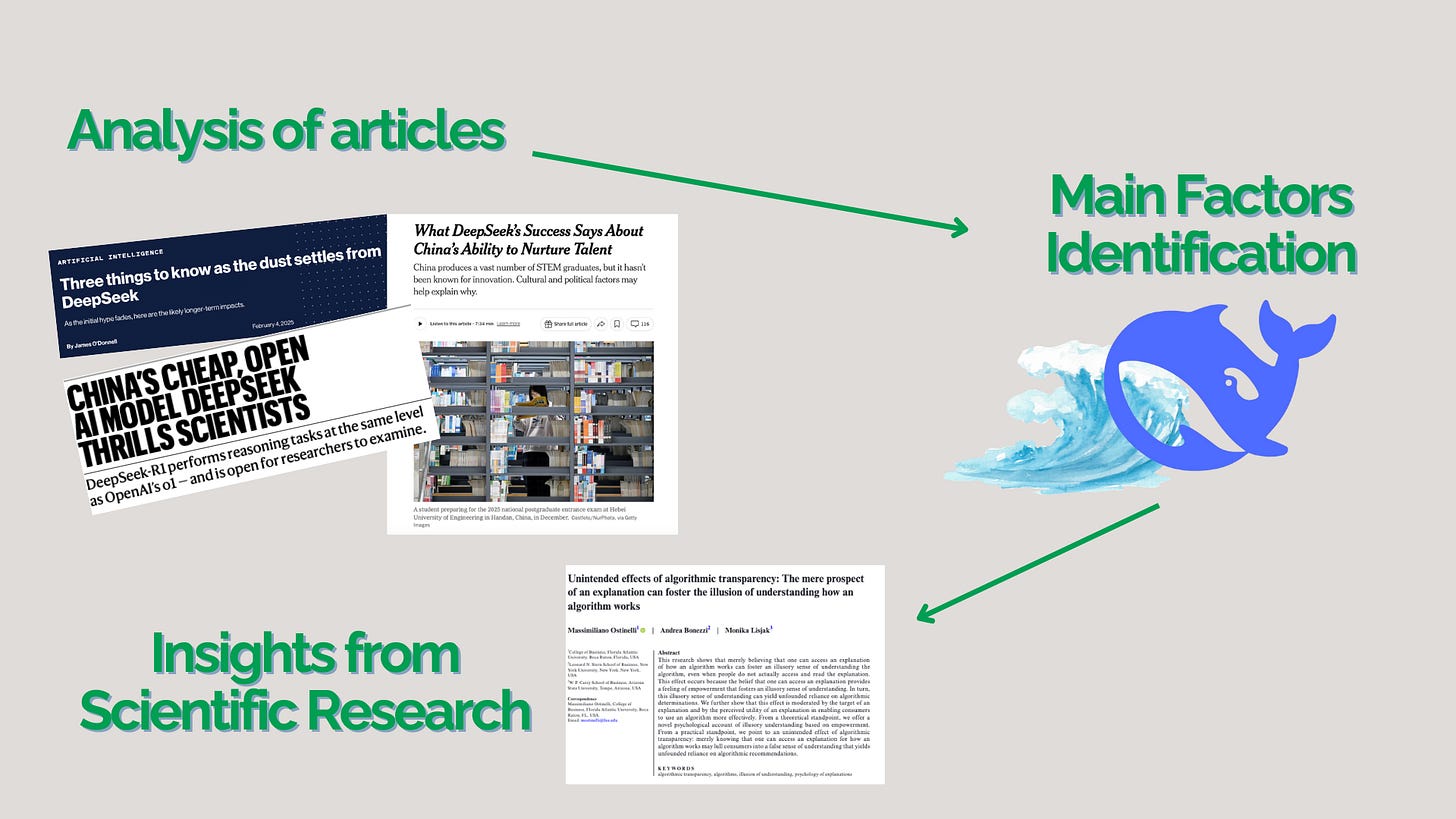

I started by analyzing over 40 articles covering DeepSeek, from established outlets like The New York Times and TechCrunch to independent Substack writers (you can find the references in the end of these piece). Some pieces focused on its structure, others on its potential to disrupt the AI ecosystem, others on its governance and usage implications.

Once I read and analyzed the articles, I tried to identify potential patterns and emerging factors that would have been interesting to explore from a user-oriented perspective.

Finally, I did some research on scientific papers that could provide insights that are related, connected, potentially applicable, even in different ways, to these topics. I tried to build a bridge between the scientific papers and the written articles, and tried to understand if there were answers to interesting questions about what emerged as a pattern.

What Did Emerge?

The articles varied widely - some were deeply technical, while others explored governance, consumer behavior, and DeepSeek impact on society. Naturally, different factors could emerge depending on how articles are analyzed, but two themes consistently stood out:

Openness. Or more precisely, the perception of openness. DeepSeek it is being discussed as a more accessible, more transparent tool compared to “closed” AI systems.

The Underdog Narrative. DeepSeek is often pictured as a challenger in an industry increasingly dominated by a few tech giants.

As anticipated, of course there were many other elements potentially to analyze, but I thought these were particularly insightful to explore and give a different, user-oriented perspective, connected to the results of the scientific papers. Don't worry, I won't bore you with a very long analysis, but I will try to get straight to the point of useful results that can be linked to these elements and understand why they are relevant, the role they played in the popularity of DeepSeek and potential effects.

DeepSeek, AI, and Openness

Artificial intelligence is increasingly present in daily life. Yet for many people, it remains a black box: it is a technology that makes decisions without clear explanations. This terminology, “black box,” has even been used in several papers. Therefore, it is not surprising that many scientists and practitioners are focused on understanding what makes certain AI models feel trustworthy and more easy to approach.

In a comprehensive review1 of AI adoption, De Freitas et al.2 (2023) identified five psychological factors shaping consumer attitudes toward AI. Two are especially interesting if we consider them related to DeepSeek:

Opacity – AI is seen as inaccessible, its internal logic unclear.

Control – Users feel that the technology is in charge, rather than themselves.

In fact, DeepSeek, whether intentionally or not, has seen a great stress of its “open source” factor, or “open weight” - as many authors, on Substack too, have specified. The language used to describe it consistently emphasizes its openness, its accessibility, and its ability to be downloaded and used in line with your own goals:

The World Economic Forum described DeepSeek as “open source, meaning it is available for anyone to download, copy, and build upon”;

Bloomberg noted that DeepSeek was released “as an open-source model, but it did not offer code or training data”;

The New York Times positioned it within the broader open-source AI movement, writing: “DeepSeek used parts of that technology as well as other A.I. tools freely available on the internet through a software development method called open source”.

As anticipated, according to many authors, DeepSeek is, technically speaking, not fully open-source.

As

clarified here on Substack:You can download the model and do fine-tuning [...]. But the data it was trained on hasn't been published. Nor the code.

Yet, in the public eye, this distinction is comprehensively blurred.

DeepSeek is perceived as more transparent, more controllable, more flexible, regardless of the extent to which this could be technically completely correct. And this could have had a significant influence on user perceptions. How? Let’s see what fascinating studies say.

In reading the articles in this issue and potentially related papers, I was surprised once again (as I always am) at how science and studies offer fascinating results through which to construct a lens for reading and interpreting certain phenomena, or simply illuminating ideas for inspiration. If we look, for example, at the field of consumer research, we see how the transparency factor (that here we could relate to the openness one) is so important in the relationship with technologies that even interventions that are seemingly not so strong as to elicit responses cause significant effects. For instance, research show that simply knowing that an explanation exists — even without reading it — creates a sense of understanding of Artificial Intelligence. Furthermore, looking at results in studies on cost transparency, it is shown that cost transparency reinforces perceptions of fairness and shapes customers’ emotional response to a product. Again, this is particularly interesting as many media outlets have highlighted the issue of DeepSeek’s costs, which are reportedly much lower than those of other companies like OpenAI.

Finally, there is the interwoven theme of control. As stated by Zimmermann et al. (2023) users accept more smart technologies when they feel a sense of control. Imagine for example that you have activated an automatic vacuum cleaner. The mere fact of being able to intervene on the algorithm or intervene on some basic setting that controls it could actually give a feeling of greater control, that it is you who decides, and not the technology.

Academics, professionals and journalists read analysis like this one on AI and how it impacts our lives every week. Join the community by subscribing for free.

Therefore, intuitively, the ability to host the DeepSeek model locally - even if users don’t know everything about it - sends a potential powerful signal of accessibility. Thus, a signal of transparency and control. The controversy over whether DeepSeek is truly open-source could not be so crucial in users’ views.

The perception of its peculiarity could.

DeepSeek, the underdog

A small organization. One that operates quietly, away from the spotlight. It pushes forward, constrained by limited resources, yet determined to achieve the best possible result. Across from it stands a giant - one whose influence stretches across industries, whose economic and cultural dominance grows by the day. A competition with uneven stakes. A battle between David and Goliath.

Now, in reading that description, who came to your mind? In the AI world, DeepSeek intuitively fills the role of the resource-strapped challenger, while OpenAI looms as the industry’s entrenched leader.

The contrast feels almost obvious. DeepSeek is framed as the outsider, up against the colossus: it’s competitor is a company with global infrastructure, billion-dollar partnerships, and an undeniable lead in the race for artificial intelligence dominance. This image is clear in our minds because, even in a very subtle way, this competition has been underlined by several articles and analyses. Not only in terms of costs, investments and size of the team - again with different considerations on the actual difference, compared to the perceived one - but also considering the influence that companies like Google, OpenAI or Microsoft exert at the moment. DeepSeek, could be perceived as disadvantaged. As emerging from difficulties. As a challenger. In a word, as an underdog.

But here’s the real question: Does this narrative help DeepSeek?

Psychologists and marketers have revealed several insights into so-called "underdog branding", particularly interesting for the "DeepSeek case". Their findings are fascinating: in many cases, when people see a company as disadvantaged but determined, they connect with it on a deeper level.

For instance, Paharia et al. (2011) show that that brands perceived as fighting against the odds inspire stronger identification, particularly among people who see themselves as facing similar struggles.

This is probably why DeepSeek’s resonated image in media could have initially have helped its popularity. Users could see partly its product as a new challenger, rooting for innovation and lower prices.

However, we should not limit ourselves to considering this narrative as a merely communicative aspect. Indeed, its relevance is potentially broad, deep and generally could reinforce the strategy in the market: in the field of Corporate Social Responsibility, “small companies” emphasizing user-centered narratives receive outsized support, while large firms face greater backlash when they are seen as out of touch or untrustworthy. DeepSeek, whether intentionally or not, could have benefited from this dynamic. In light of the ethical questions underlying DeepSerek's training, this could be particularly important, and also lead to a series of analyses on the possible paradoxical nature that this coexistence of narratives could bring.

A final note

The technical analyses on DeepSeek and the various articles written about it are fascinating. In this analysis, I tried to reconnect the dots in the perspective of what users - I would say numerous - could have perceived, and how some factors beyond merely technical or performance ones could impact perceptions at a time when the AI tools market is starting to take an initial interesting shape. Once again, the insights from some scientific studies have provided an enlightening perspective, and I would like to virtually thank the authors of the papers and articles of various types that led to the construction of this issue. For me this issue was also an experiment with a new format, which I hope you enjoyed. Experimenting has been and will be one of my goals for 2025 on Substack, and I will continue to do so in different forms like in this case. Any comments you may have on this issue or in general are of inestimable appreciation.

There is still much to analyze, read and discover, at a time when DeepSeek has just emerged. But regardless of what will happen or what will emerge, one thing does not see many doubts: the whale has at least shown its tail and attracted attention.

Who knows, maybe other creatures will do the same. Or something different.

References

Media Articles

WEF (2025) - What is open-source AI and how could DeepSeek change the industry?

Bloomberg (2025) - How DeepSeek and Open Source Models Are Shaking Up AI

The New York Times (2025) - Meta Engineers See Vindication in DeepSeek’s Apparent Breakthrough

The New York Times (2025) - How Did DeepSeek Build Its A.I. With Less Money?

WEF (2025) - How AI’s impact on value creation, jobs and productivity is coming into focus

MIT Technology Review (2025) - How DeepSeek ripped up the AI playbook—and why everyone’s going to follow its lead

Nature (2025) - How China created AI model DeepSeek and shocked the world

Nature (2025) - Scientists flock to DeepSeek: how they’re using the blockbuster AI model

Nature (2025) - China’s cheap, open AI model DeepSeek thrills scientists

BBC (2025) - DeepSeek: What lies under the bonnet of the new AI chatbot?

The Washington Post (2025) - The hottest new idea in AI? Chatbots that look like they think.

Science (2025) - Chinese firm’s faster, cheaper AI language model makes a splash

Guardian (2025) - We tried out DeepSeek. It worked well, until we asked it about Tiananmen Square and Taiwan

CNN (2025) - What is DeepSeek, the Chinese AI startup that shook the tech world?

TechCrunch (2025) - DeepSeek: Everything you need to know about the AI chatbot app

TechCrunch (2025) - DeepSeek’s R1 reportedly ‘more vulnerable’ to jailbreaking than other AI models

Vox (2025) - You’re wrong about DeepSeek

The Verge (2025) - Why everyone is freaking out about DeepSeek

From Substack

The Issues With DeepSeek: Unsettling Responses With A Different Worldview by

Beyond the AI Hype: What DeepSeek Really Means for Our Future by

I don’t believe DeepSeek crashed Nvidia’s stock by

DeepSeek's moment: Beyond the $5.6M hype and market panic by

🏮DeepSeek: everything you need to know right now. by

andThe race for "AI Supremacy" is over — at least for now. by

Constraints to Innovations: Software & Architectural Elegance of the DeepSeek V3 Model by

🌊 China’s DeepSeek AI Shakes Up the Game by

andHow DeepSeek Caught Silicon Valley Off Guard by

andIs DeepSeek the new DeepMind? by

Making the U.S. the home for open-source AI - by

DeepSeek: How China's AI Breakthrough Could Revolutionize Educational Technology by

DeepSeek R1: The AI Disruption No One Saw Coming by

DeepSeek: Frequently Asked Questions by

AI Roundup 103: The DeepSeek edition by

Who’s Winning the AI War: 2025 (DeepSeek?) Edition by

How Deepseek Just Changed AI Forever -And Big Tech Is Powerless To Stop It by

DeepSeek and the Future of AI Competition with Miles Brundage by

Open-Source AI and the Future by

DeepSeek Is Chinese But Its AI Models Are From Another Planet by

Debunking 10 Popular Myths About DeepSeek by

Papers

Bonaccorsi, A., & Rossi, C. (2003). Why open source software can succeed. Research Policy, 32(7), 1243-1258.

Chen, C., Tian, A. D., & Jiang, R. (2024). When post hoc explanation knocks: Consumer responses to explainable AI recommendations. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 59(3), 234-250.

De Freitas, J., Agarwal, S., Schmitt, B., & Haslam, N. (2023). Psychological factors underlying attitudes toward AI tools. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(11), 1845-1854.

Hart, J. L., Esrock, S. L., D’Silva, M. U., & Werking, K. J. (2001). David and Goliath revisited: Grassroots consumer campaign battles a corporate giant. American Communication Journal, 4(3), 1-20.

Jung, H., Bae, J., & Kim, H. (2022). The effect of corporate social responsibility and corporate social irresponsibility: Why company size matters based on consumers’ need for self-expression. Journal of Business Research, 146, 146-154.

Kervyn, N., Fiske, S. T., & Malone, C. (2022). Social perception of brands: Warmth and competence define images of both brands and social groups. Consumer Psychology Review, 5(1), 51-68.

Kim, Y., Park, K., & Stacey Lee, S. (2019). The underdog trap: The moderating role of transgression type in forgiving underdog brands. Psychology & Marketing, 36(1), 28-40.

Kozinets, R. V., Ferreira, D. A., & Chimenti, P. (2021). How do platforms empower consumers? Insights from the affordances and constraints of reclame aqui. Journal of Consumer Research, 48(3), 428-455.

McGinnis, L. P., & Gentry, J. W. (2009). Underdog consumption: An exploration into meanings and motives. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 191-199.

Ostinelli, M., Bonezzi, A., & Lisjak, M. (2024). Unintended effects of algorithmic transparency: The mere prospect of an explanation can foster the illusion of understanding how an algorithm works. Journal of Consumer Psychology.

Paharia, N., Keinan, A., Avery, J., & Schor, J. B. (2011). The underdog effect: The marketing of disadvantage and determination through brand biography. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 775-790.

Patel, J. D., Trivedi, R., Malhotra, S., & Jagani, K. (2024). Understanding underdog brand positioning effects among emerging market consumers: a moderated mediation approach. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 33(8), 1013-1026.

Pfannes, C., Meyer, C., Orth, U. R., & Rose, G. M. (2021). Brand narratives: Content and consequences among heritage brands. Psychology & Marketing, 38(11), 1867-1880.

Simintiras, A. C., Dwivedi, Y. K., Kaushik, G., & Rana, N. P. (2015). Should consumers request cost transparency?. European Journal of Marketing, 49(11/12), 1961-1979.

Yang, L. W., & Aggarwal, P. (2019). No small matter: How company size affects consumer expectations and evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(6), 1369-1384.

Zimmermann, J., Görgen, J., De Bellis, E., Hofstetter, R., & Puntoni, S. (2023). Smart product breakthroughs depend on customer control. MIT.

Thank you for reading this issue of The Intelligent Friend and/or for subscribing. The impact of AI in our daily life is a crucial topic and I am glad to be able to talk about it having you as a reader.

Has a friend of yours sent you this newsletter or are you not subscribed yet? You can subscribe here.

Surprise someone who deserves a gift or who you think would be interested in this newsletter. Share this post with your friend or colleague.

“et al.” stands for ‘and colleagues,’ and is a common form to refer to co-authors of a scientific article.

A “literature review”, in simple words, is a type of academic paper that organize, report (and potentially build models to better understand) what scientists have said up to that point on a given topic. For example, if I study how colors impact the choice of products, I might decide to write and submit for publication to a scientific journal an article that describes what scientists have obtained now related to colors and product choices.

There is a certain sense of psyop theatre to the rush of coverage, I doubt many people/journalists outside the industry understood the details however. Mostly I think it sold well as a story, as on it's face, it proved that you could do more with less. Regardless of whether you believe the numbers. It's obvious that DeepSeek has innovated in a space and place that few expected. The very nature of the Chinese tech giants seems to be low paid drudge work and rigid structures. Compared to the collegiate atmosphere spoken about at DeepSeek. That and they gave away the details of how they did what they did in the paper they published. You don't need the code, as the real innovation was in process. At least from my understanding of it. V3 came out to almost no fanfare in December, it was R1 that caused the ruckus. Decent model as it goes, I have a version distilled into Llama 3.1 70B at 5Q_KM running on a 3090 it's very verbose and sea change compared to what came before.

https://thesequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-opinion-489-crazy-how (paid)

Hand coding PTX and NCCL on GPU allowed DeepSeek R1 to efficiently train its massive model on a cluster of 2,048 H800 GPUs over just two months.

DeepSeek in China is the ah-ha moment some of us experienced with ChatGPT. Young people using it for therapy for example, is not uncommon. It more or less disrupted other apps there, not just globally.

I'm not sure Western people can fully understand what DeepSeek means tbh. DeepSeek is a rally cry for China AI, open-source and many other things including China's homegrown semi independence and national strategy.