The day's work was truly exhausting. You took the subway home, and it was packed. Or by car, but the roads were clogged. Ready to unwind with a nice evening to "pamper yourself," you decided to make something delicious and watch your favorite series. Perhaps, a vegetarian recipe. You thought about it on the subway or in the car. And though you squeezed yourself to think of something creative, you couldn't come up with anything.

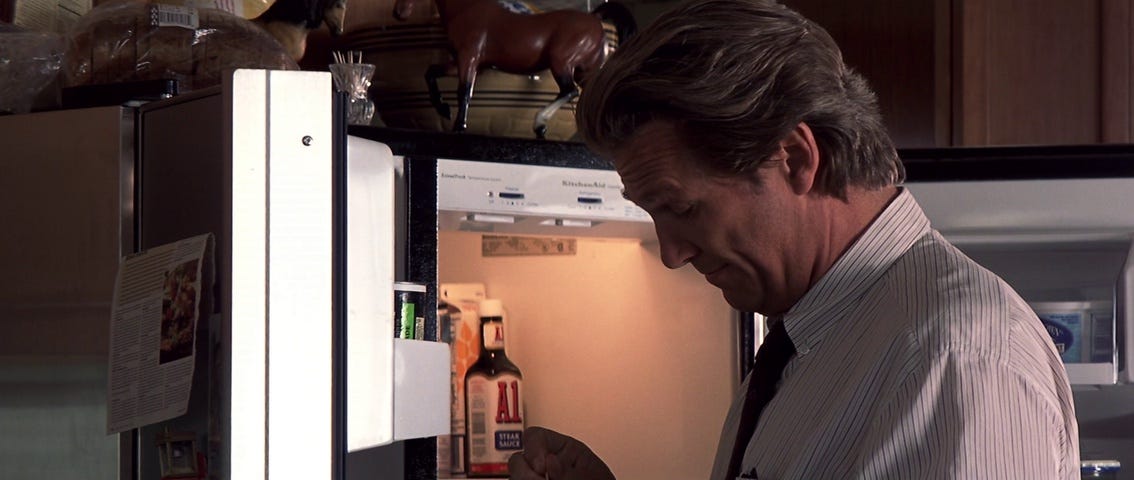

You get home thinking about a possible something to cook. You suddenly hear a bell. It's the sound of the new smart fridge. A high-tech product with a neat design and opaque cores, as well as an advanced, shiny screen. This truly innovative refrigerator model more or less recorded the opening hours by estimating the dinner time.

So, unintentionally, it did in fact suggest something new, unexpected, unpredictable. For example, it helped you with the suggestion of a "healthy" eggplant parmigiana recipe.

In short, though, your fridge learned what you did. It processed the data. And it acted in a not-highly-predicted way. It acted by its algorithm. And it did it creatively.

Learning is not always better

This image of you approaching a new, advanced fridge model may have evoked mixed feelings. You might have thought, "Great, my fridge just gave me the perfect solution!" Or perhaps, its unpredictability left you slightly perplexed. You didn't quite appreciate it. After all, a refrigerator, no matter how smart, should primarily keep food cold. That steak you love to grill. The broccoli you always promise to make palatable, even for the pickiest eaters. And the butter for all those delicious desserts you make for your friends.

As you might imagine, this potential difference in opinion arises directly from your fridge's ability to learn. Your refrigerator hasn't just stuck to its basic functions; it's used its algorithm to identify patterns in your behavior. But it went a step further too. It made a suggestion, tailoring its notification to your actions. Essentially, your fridge has showcased a "high-adaptivity algorithm".

In their fascinating recent study, Melanie Clegg and colleagues studied exactly how consumers feel about products powered by algorithms that can adapt and learn.

As anticipated, the crucial distinction is the difference between high-adaptivity algorithms, which learn and evolve over time, and low-adaptivity algorithms, which are pre-programmed and fixed.

Low-adaptivity algorithms function like precise rule-followers: think for instance of a smart thermostat that sticks to "if-this-then-that" rules;

High-adaptivity algorithms, instead, are akin to learners: they change their parameters based on the feedback given by the user.

This distinction is important for understanding why we trust some products more than others, why we may prefer some smart features or tools over others, and what this means for many industries.

Creative or predictable, that is the question

However, while the study by Clegg et a. (2024)1 identified an interesting effect, it also revealed when this effect might change direction or strength. To go into this, let's leave the fridge aside for a moment. Think about the next phase of your relaxing evening.

Despite your varied reactions to the appliance, you've prepared dinner. Your healthy eggplant parmesan is ready and you've already sent it to your group of friends, inviting them to replicate this wonderful dish. You go on Netflix to watch a movie. Here too, you're short on ideas: today's work has really tired you out! So, what happens if we turn our attention to Netflix's algorithm instead of our fridge's?

If you're part of the 'party' against a fridge that learns and adapts, what do you think about the platform? Should it stick to standard or trend-driven recommendations, or would you like something more personalized? Probably, if, for example, you love The Holiday, you'd want other suggestions that hint at Christmas comedies that could give you similar feelings. Or even romantic comedies in general.

In short, the key idea is clear: the things you actually think a product can do for you might change your mind about the 'learning ability' of its algorithm.

And that's exactly what the researchers investigated.

“The things a product can do for you” is called it is more properly called by authors as POR: product outcome range (POR).

For example, a smart lock has a narrow POR (it either locks or unlocks);

A voice assistant (like Alexa), instead, has a wide POR (it can set reminders, play music, and answer questions).

Do you do more things? You need to learn then!

The researchers conducted six studies, systematically varying the types of algorithms (high-adaptivity vs. low-adaptivity) and the nature of the tasks or products. Participants were given scenarios where the product either demonstrated creativity (e.g., suggesting novel recipes) or predictability (e.g., consistently locking doors). Importantly, the researchers also manipulated product outcome range to see how adaptivity preferences shifted in narrow versus broad contexts.

The team found that high-adaptivity algorithms were often seen as more creative, and therefore ideal for products with wide PORs. Conversely, low-adaptivity algorithms, prized for their predictability, were preferred for tasks demanding predictability, like locking a door.

A final note

As you may have noticed, this issue is shorter than usual. I had promised myself as a sort of New Year’s resolution to experiment with different formats, personal reflections and essays of various kinds. I hope you like it and I would be really excited to know what you think of these “experiments” (and in particular of this one) in the comments!

The Highlight 🔦

This is the section where I highlight some of the great issues I read during the week from other authors on Substack, and that I would like to share with you.

A fascinating issue on habits and New Year's resolutions, by

.

’s 100th roundup, which you can't miss, like all his future ones.

As always, a creative, inspirational and profound reflection that will make you think, by

.

For those looking for some reading suggestions for the beginning of the year, or wanting to spend some gift vouchers, this list could be really stimulating! By

.

A truly interesting and thought-provoking analysis on a generation, by

.

Thank you for reading this issue of The Intelligent Friend and/or for subscribing. The relationships between humans and AI are a crucial topic and I am glad to be able to talk about it having you as a reader.

Has a friend of yours sent you this newsletter or are you not subscribed yet? You can subscribe here.

Surprise someone who deserves a gift or who you think would be interested in this newsletter. Share this post with your friend or colleague.

Clegg, M., Hofstetter, R., de Bellis, E., & Schmitt, B. H. (2024). Unveiling the Mind of the Machine. Journal of Consumer Research, 51(2), 342-361.

Thank you for the kind mention.

Good insights on the acceptability of algorithms. Now, I need to weave this into my sci-fi book!