The Intelligent Friend - The newsletter that explores how AI change our daily life, only through scientific papers.

Intro

Welcome to this new issue of The Intelligent Friend. Allow me to send a big virtual greeting to all the new people who have joined our wonderful community: thank you so much, sincerely!

As you may have guessed from the title of this issue, it will be a slightly different piece. In The Intelligent Friend we try to better understand how AI influences our daily lives. How it impacts our relationships, our choices, our behaviors. And we do it through the work of many scientists, whose research is the absolute protagonist, every Sunday (the day this newsletter is published).

However, the today’s issue is part of a particular "series". Some time ago I wrote an essay on why I love reading papers. Not only did I enjoy writing it, but many readers and writers appreciated it and even contacted me privately to discuss it. Therefore, today I’ll continue this series of personal essays with a second chapter in which, instead, I will try to share with you why my heroes are scientists, and why the consequences of this are anything but obvious.

Is your hero… a scientist?

As a child, I loved atlases. I spent hours reading them, leafing through them, drawing on them. As unusual as it may seem, it was one of my favorite activities, if not the favorite, for a period of time.

In Italy (where I come from) I clearly remember that for a while they were very popular. I didn't love all atlases, though. I was particularly fond of animal atlases. For example, wild animals, rare species, extinct animals. And, like any self-respecting child, dinosaur atlases. However, jungle animals were absolutely my favorite team. Over time, my passion for atlases faded. More than anything, I would say it was replaced. Or, more precisely, it evolved.

In fact, as I grew up, I discovered a common element. The fantastic features of the rainforest frog that I admired. The tracks of Australopithecus. The existence of the Dodo. The speed of the leopard. They were observed or studied by one large, great, wonderful category: scientists.

This discovery has never been immediate or direct, but, naturally, gradual. In fact, for a while I thought that "scientist" was a specific and - at the same time - “comprehensive” profession. That there were not many "specializations", such as "biologist" or "paleontologist". The fact is that, summing up, the figure of people who spent their lives searching and discovering, has been a constant in my life. Therefore, it is not a surprise maybe in your view, that I’m trying to pursue an academic career (currently I am a Marketing Research Assistant).

However, I would like to point out that the two things are not exactly superimposable. The reasons why scientists are my heroes naturally influence my choices, but the process is not reversed: they are not my heroes because I would like to pursue an academic career. The reasons are independent of this choice.

Scientists have always been my models. I try to read a lot of scientific papers, not only related to what I study or my work, I constantly read popular magazines (like New Scientist), and I like to browse through books written by researchers.

Scientists are "heroes" who do not have a cape, but a white shirt - or a sweater or something else, depending on taste and field.

In short, today we are going on a different journey. Rather than focusing on Superman and Wolverine, we will think about those who examined them. Those who build the armor. Who study the "potions". Who silently change the world.

The Superpower of Curiosity

I promised myself not to write a too long piece, so, I will go straight to the three main reasons behind the title given to this issue.

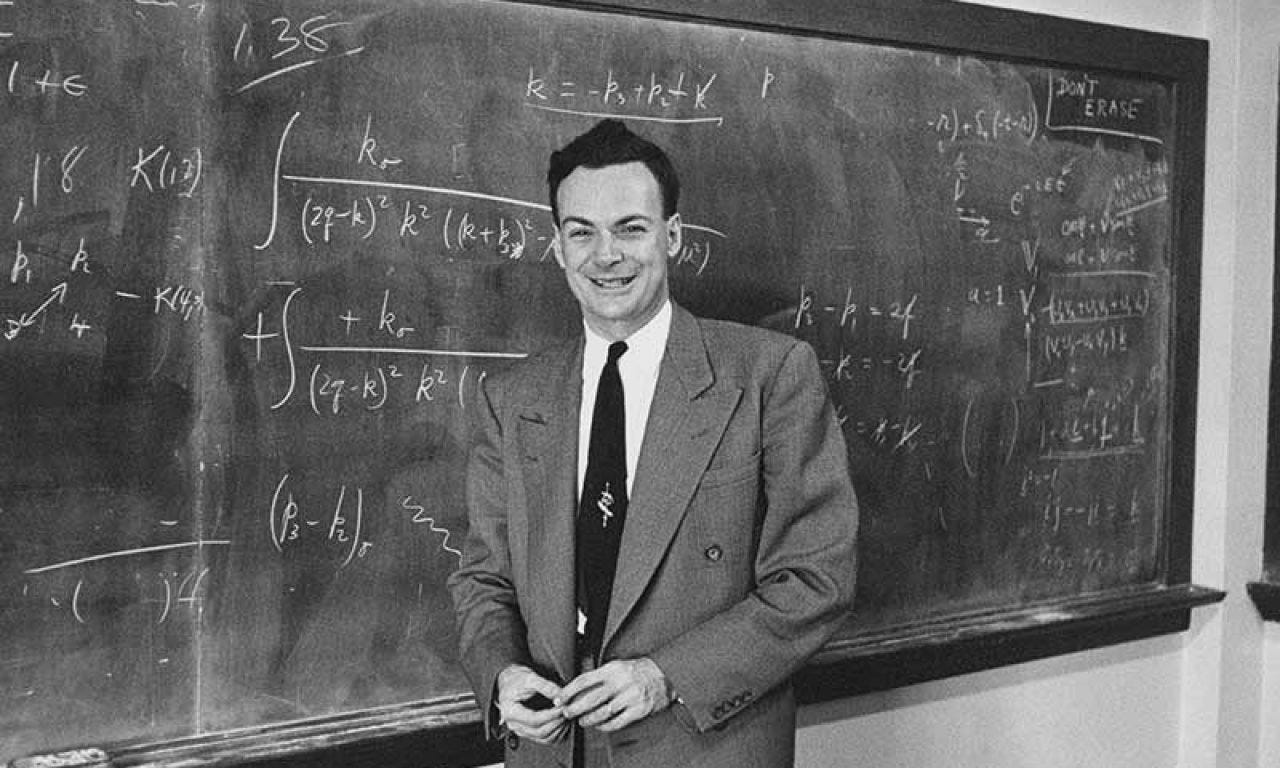

Let's start, of course, with curiosity. To illustrate the concept, Richard Feynman had some really enlightening words.

Study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible.

I think this is one of the sentences that best describes the vision I have of science and, above all, of the work of scientists.

Scientists, first and foremost, have the superpower of curiosity. Yes, a superpower. Because, very often, this curiosity knows no bounds. People who do research - of any type and field - are driven first and foremost by the desire to know. And not to know everything, but to know more about something, and to be able to spread it. This difference is fundamental.

Scientists don’t aspire to a generic understanding of the world. They aim to dive deeply into the particulars of their chosen field, to uncover something potentially new. Whether it's string theory, lemurs' adaptation to environmental problems, the influence of language certainty on interactions, or how AI is changing the way we create content, our heroes focus on a field and a topic that is, very often - if not always - incredibly specific. And they do it with infinte dedication. With boundless interest. With absolutely contagious energy. Speaking very often with people doing a PhD or post-doc I was absolutely struck by the way they shared the research results they had chosen. Of a paper they were looking at. Of the work of another scientist.

Furthermore - and this is fundamental - it is not just about wanting to know, but wanting to spread.

Scientists are curious and spread what they achieve through publications. And not only that. Scientific dissemination, for example - in which some of my friends and writers told me this newsletter would also fall - is increasingly growing. Not only because there are more people interested in listening. But also because there are more "men and women of science" who want to do it.

It is no coincidence that one of my idols is also David Attenborough, British broadcaster and biologist, protagonist of several documentaries that you can also find on Netflix, including "A Life on Our Planet".

The Patterns’ Research

But Superman, Spiderman or Iron Man do not stop at just one superpower. They go beyond. They go and fight battles. They immerse themselves in incredible challenges. Well, that specific challenge that makes scientists incredibly dedicated heroes for me is the search for patterns. Scientists, driven by the "superpower" of boundless curiosity, immerse themselves in identifying patterns from data or observations.

It is independent of whether it is research on the effects of microbacteria on digestion, the footsteps of Homo habilis in Africa or the effects of walking on mental fatigue. What is incredibly overwhelming is the dedication to trying to abstract, generalize, illuminate starting from what you have. And if we go even further into the methods used, increasingly varied, we will discover even more intriguing aspects.

I will explicit better this with an example. Recently, in several articles in consumer research, the importance of studying the influence of language more has been highlighted. This has also been done in conjunction with the fact that LLMs offer new spaces for so-called computational approaches that could provide new research insights. And this makes the search for patterns and cause-effect relationships shine brighter. This example underline how, for researchers, not only is there a constant commitment in the discovery, but also that techniques of analysis can vary and give even more nuance.

It is not just about connecting the dots. But also the ways in which these can be connected. Redesigned. Revised.

Digging before constructing

Finally, an aspect that I particularly appreciate about scientists is the theme of "construction". In research, you do not start from scratch. In research, you start from the work of other scholars. This, for me, has always been incredibly valuable. The papers of other scientists are often inspirational, revealing, or simply stimulating to reflect1. This construction, very often, makes the work of the scientist impregnated of dialogue, interaction, network. Of course, it should be specified that this depends a lot, as for all aspects of this issue, on the type of work, research, field in which one is immersed.

But as a core principle, building on previous work or collaborating with other scientists is crucial, more and more so today.

You can't build a beautiful palace if you don't know that the ground is solid. And so a careful study of the previous work can allow you to discover what research really reveals, what it still has to say, what it may have gone wrong.

There is a continuous process of exploration, criticism, self-criticism. Of deep and intense re-examination. This exploration aimed at interaction, reconstruction, broadening or deepening is the impetus that scientists have.

Scientists, on a daily basis, immerse themselves in their work. Immersing yourself in their work is something reciprocating the commitment, enlightening and, as much as it may surprise you, often fun and intriguing.

Thank you for reading this issue of The Intelligent Friend and/or for subscribing. The relationships between humans and AI are a crucial topic and I am glad to be able to talk about it having you as a reader.

Has a friend of yours sent you this newsletter or are you not subscribed yet? You can subscribe here.

Surprise someone who deserves a gift or who you think would be interested in this newsletter. Share this post with your friend or colleague.