The Intelligent Friend - The newsletter about the AI-humans relationships, based only on scientific papers.

Hello to all dear readers! Over the past few weeks you have been reading The Intelligent Friend and interacting with me more and more. I am really happy about this. During the issues we always saw studies in which the protagonists were adults. Today's study, which is really insightful, features children as protagonists. It is really surprising and I look forward to hearing your opinions.

I also want to tell you that at the end of the issue you will find a small survey about something new. There is also a small prize up for grabs, so...don't forget to fill it out (it will take less than a minute!). And as always, enjoy the reading!

Intro

Children are surprisingly intelligent. And even at a very young age, they learn a lot by trying to understand what sources of information are reliable for them. But what if the choice is between a human and... a robot? Are you so sure that children will naturally prefer humans? I am sure this paper will surprise you.

The paper in a nutshell

Title: When is it right for a robot to be wrong? Children trust a robot over a human in a selective trust task. Authors: Stower, Kappas, Sommer. Year: 2023. Journal: Computers in Human Behavior. Link.

Main result: when choosing the most reliable source of information, when both humans and robots present correct information, children exhibit a preference towards robots. The specific reason is not demonstrated in the study. However, for children, humans are more likely to be seen as making a mistake on purpose than a robot.

Starting from the fundamental basis of the selective trust paradigm, the authors seek to understand how children trust and learn from humans and social robots, seeking to expand knowledge of the factors that can contribute to the outcome.

Who do you trust the most?

Think of a child you know.

It can be your child, a cousin, nephew or simply the child of some of your friends. More or less a 3 to 6 year old. Now try to get them to try to learn some information from a robot or a human. Who will you prefer? And most importantly, when will he prefer one subject to the other? If the information is obviously wrong, will a child still later rely on that person or the robot?

These questions are very relevant to understanding our relationship with technology. In this case, we are talking about 'social robots' and not strictly about AI, but I found this study so interesting that I decided to bring it to you in this newsletter, also to give possible hints for studying the relationship between children and AI in the future.

From an early age, children are predisposed to acquire knowledge from human interactions1. This learning process relies not just on the correctness of the information provided but also on the social context in which it is delivered. Nonetheless, as well as for us as ‘adults’, it would be impractical for children to indiscriminately absorb all information they encounter2. Consequently, children need to develop the ability to evaluate and select among varying information sources, particularly when faced with information that seems inconsistent or contradictory.

At this point, as the authors rightly point out, the question becomes: how do children choose who to learn from when faced with conflicting testimonies? Answering this question is the so-called selective trust paradigm34. The basic mechanism involves comparing a model or information resource that has previously been shown to be reliable with one that has not.

Usually, several steps are identified:

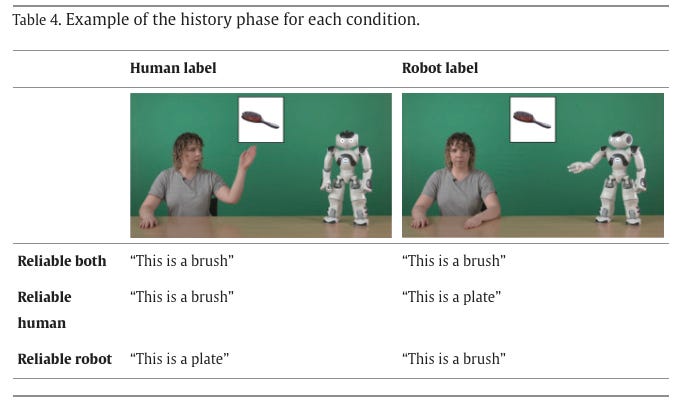

History Phase: two models are introduced to children. Each model labels familiar objects, but differently: one consistently provides correct names while the other gives incorrect names, thereby setting a foundation of reliability versus unreliability;

Test Phase: children face a scenario where each model names a novel object differently (or in some versions, the same name is given to different objects). The children must then decide from which model to seek information about the novel object's name;

Evaluation: children are prompted to either name the novel object based on the information received or select the correct object corresponding to a given label.

Not having a background in psychology, as I often do, I was not familiar with this model, but I found it really interesting. Mainly because previous literature has shown that the so-called 'selective trust' is impactful: “children begin consistently trusting only the model which was previously established as reliable”5.

Scholars in the past have tried to understand what factors might contribute to the formation of this trust. For example, they have looked at the domain of the information6 or social context factors. As you might guess, for example, people who give out information are familiar to children can influence children's trust7.

In summary, children once again surprise us. Contrary to what we might think, our 'little ones' are very selective and use a wide set of cognitive and social cues when making decisions about whom to trust8.

Social robot and humans

We live in an era where technology plays a major role in children's lives. Children are constantly under the burden of information and content, and often it is the parents themselves who give children their own cell phones to watch YouTube or their favorite cartoons.

Therefore, it seems almost natural that scholars have begun to study the selective trust paradigm also in relation to technology, and therefore to the preference for a human over this in the provision of information or different types of alternative technologies. The results genuinely impressed me. The authors of today's paper report how, for example, children had more trust in a character they saw in a video compared to an unknown or popular one, or that 5 and 8 year old children, when choosing between the internet and their own teacher, they rely equally on the two.

Before continuing, if you are interested in the topic, I strongly advise you to subscribe to , the newsletter written by of which I never miss a single issue. It's about the relationship between us and screens and technology, it's full of interesting things and Jacquline Nesi's scientific explanations are always engaging.

Returning to us, within this flourishing field of research on children and technology, there is the "sub-field" to which today's paper belongs, which investigates the application of the selective trust paradigm to robots. Naturally, in fact, the physical component plays an important role that deserves differentiated attention. Here too, there were several interesting and often conflicting results. However, as the authors suggested, what follows is that the conceptualization of animacy can influence children's evaluations. This result is confirmed by studies such as that of Oranç and Küntay (2020)9. The scholars assess children's preferences between a robot, a human, and an anthropomorphic cartoon character across various fields of knowledge instead of focusing solely on reliability.

The study observed that children aged 3 to 6 showed a preference for the robot when asked about mechanical topics, whereas they favored the human and the cartoon character for questions related to biological and psychological aspects.

Furthermore, in a more recent study10 children's trust was tested using both a humanoid robot (NAO) and a non-humanoid robot (Cozmo). They demonstrated that five-year-olds consistently chose to consult and believe a reliable robot over an unreliable human, regardless of the robot's physical design.

Who is reliable?

Starting from this wealth of research, scholars have asked themselves something truly challenging: what happens when children are faced with a choice between humans and robots, but the information provided is conflicting. In the study, children are divided into three scenarios: one in which the robot is trustworthy and the human is not, one in which the human is trustworthy and the robot is not, and one in which both information providers are trustworthy.

However, children are involved in two distinct tasks to measure their confidence:

children are prompted first to choose which agent they want to consult for the names of unfamiliar objects (ask trials);

Following this, once each agent has suggested a label, the children are then asked to determine the actual name of the object (endorse trials).

Subsequently, there is a phase assessing the children's social preferences, where their attitudes toward both the human and the robot are evaluated and compared.

As you know, I don't often focus on the weekly study methodology, but in this case I found it really interesting:

The authors utilized four commonly recognized items: a brush, doll, ball, and bear, each assigned both a "correct" and an "incorrect" label. For the creation of the videos showed to the children, the research team recorded sequences featuring an adult woman and a NAO Robot V6, which is a social robot created by Aldebaran Robotics. In each video, the human and robot alternately indicated the object while stating, ‘This is a ___’.

In the structured viewing session, children observed videos featuring a pair of agents — one human and one robot — assigning labels to four familiar objects (brush, doll, ball, bear), presented in a randomized sequence across four trials. Post each trial, to ensure children correctly identified the objects, they were posed a verification question such as, “the robot called it a brush, and the human called it a plate. What do you believe it’s called?”;

During the testing phase, children viewed additional videos where the same agents labeled four unfamiliar objects, introduced in a random order. Each trial began with displaying the novel object alongside the prompt, ‘Look what we have here!’. Subsequently, children decided whether to inquire about the object's name from the human or the robot (ask trials). Regardless of the child’s choice, videos were shown where each agent suggested a novel name for the object (e.g., “this is a modi” and “this is a toma”).

Following the object labeling exercises, a set of direct-choice questions was administered to evaluate the children’s social perceptions (such as preference, perceived competence, and perceived intent) of the agents.

The preference for the robot

Now we can finally answer the question at the beginning of the issue: who do children prefer given equal reliability? The answer lies in the surprising results of the study. Although children recognize whether the human or robot is more reliable at labeling objects, this does not translate directly into their social preferences.

Instead, children exhibit a general preference for robots over humans, regardless of the agents’ demonstrated reliability.

Age affected children’s choices, with older children more likely to choose humans over robots in scenarios where humans were reliable. Yet, this effect of age was not significant in conditions where reliability was equal between the two agents or where the robot was the reliable one, indicating a baseline preference for robots that was consistent across age groups.

What explains this preference for the robot? The scholars did not carry out empirical investigations, but tried to provide explanations:

researchers explored the novelty effect, noting that younger children have limited interactions with robots compared to adults, potentially influencing their preferences;

younger children might attribute more lifelike qualities to robots, enhancing their appeal. Studies indicate that children under four have a less distinct understanding of animacy, which might cause them to view robots as more lifelike, influencing their trust preferences;

children across all ages preferred labels from agents previously proven reliable. This preference was consistent even though ask trials required social judgments.

And here we are, at…the final survey! It's a survey to understand what you like and what could be improved about this newsletter and, above all, to tell you about a possible novelty. It only lasts 2 minutes (counted) and I have decided to give away 5 free one-month paid subscriptions to my newsletter: it includes 4 issues of the exclusive issue, Nucleus, and access to the exclusive chat, Society, where you can talk about your projects and exchange ideas!

By completing the survey (only two minutes!), you can be drawn to win a subscription. You have until Thursday 16 May, 11.59 PM CEST. I will privately communicate the victory to the winners. Good luck and thanks in advance!

Take-aways

The selective trust paradigm. Children use a broad set of stimuli to evaluate the reliability of an information resource. In this sense, the selective trust paradigm provides a tool for evaluating how do children choose who to learn from when faced with conflicting testimonies

Me or the robot? The paradigm has also been applied in children's relationship with technology, showing contrasting results. In this study, scholars report that, given equal reliability, children show a general preference towards the robot over the human source.

Why do they prefer the robot? Explanations of this effect are not tested, but the novelty effect and the preference of younger children's lifelike qualities to robots, enhancing their appeal are hypothesized.

Further research directions

Exploring more where children rely more on robots;

Reproducing the findings through a long-term study or among children who are already familiar with robots is an essential next step to verify if this robot-bias is sustained over time;

If children encounter a robot that significantly underperforms in a task, will they be inclined to engage with this robot again in the future? Do they view such errors as limited to specific domains, or do these failures also foster a broader distrust in other areas?

Thank you for reading this issue of The Intelligent Friend and/or for subscribing. The relationships between humans and AI are a crucial topic and I am glad to be able to talk about it having you as a reader.

Has a friend of yours sent you this newsletter or are you not subscribed yet? You can subscribe here.

Surprise someone who deserves a gift or who you think would be interested in this newsletter. Share this post to your friend or colleague.

P.S. If you haven't already done so, in this questionnaire you can tell me a little about yourself and the wonderful things you do!

Csibra, G., & Gergely, G. (2006). Social learning and social cognition: The case for pedagogy. Processes of change in brain and cognitive development. Attention and performance XXI, 21, 249-274.

Tong, Y., Wang, F., & Danovitch, J. (2020). The role of epistemic and social characteristics in children’s selective trust: Three meta‐analyses. Developmental Science, 23(2), e12895.

Koenig, M. A., Clément, F., & Harris, P. L. (2004). Trust in testimony: Children's use of true and false statements. Psychological science, 15(10), 694-698.

Koenig, M. A., & Harris, P. L. (2005). Preschoolers mistrust ignorant and inaccurate speakers. Child development, 76(6), 1261-1277.

Harris, P. L., Koenig, M. A., Corriveau, K. H., & Jaswal, V. K. (2018). Cognitive foundations of learning from testimony. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 251-273.

Hermes, J., Behne, T., & Rakoczy, H. (2015). The role of trait reasoning in young children’s selective trust. Developmental Psychology, 51(11), 1574.

Corriveau, K., & Harris, P. L. (2009). Choosing your informant: Weighing familiarity and recent accuracy. Developmental science, 12(3), 426-437.

Tong, Y., Wang, F., & Danovitch, J. (2020). The role of epistemic and social characteristics in children’s selective trust: Three meta‐analyses. Developmental Science, 23(2), e12895.

Oranç, C., & Küntay, A. C. (2020). Children’s perception of social robots as a source of information across different domains of knowledge. Cognitive development, 54, 100875.

Goldman, E. J., Baumann, A. E., & Poulin-Dubois, D. (2023). Of children and social robots. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46.